Need help? Start on our program sites:

Many foster parents know this story well: the child in your care seems to settle in beautifully for the first few weeks. They’re quiet, helpful, and follow the rules. Then suddenly, everything changes. They start acting out, breaking rules, or picking fights. Your first thought might be, “The honeymoon is over—now they’re testing me.”

But what if something else is happening? What if the child isn’t being defiant—they’re grieving?

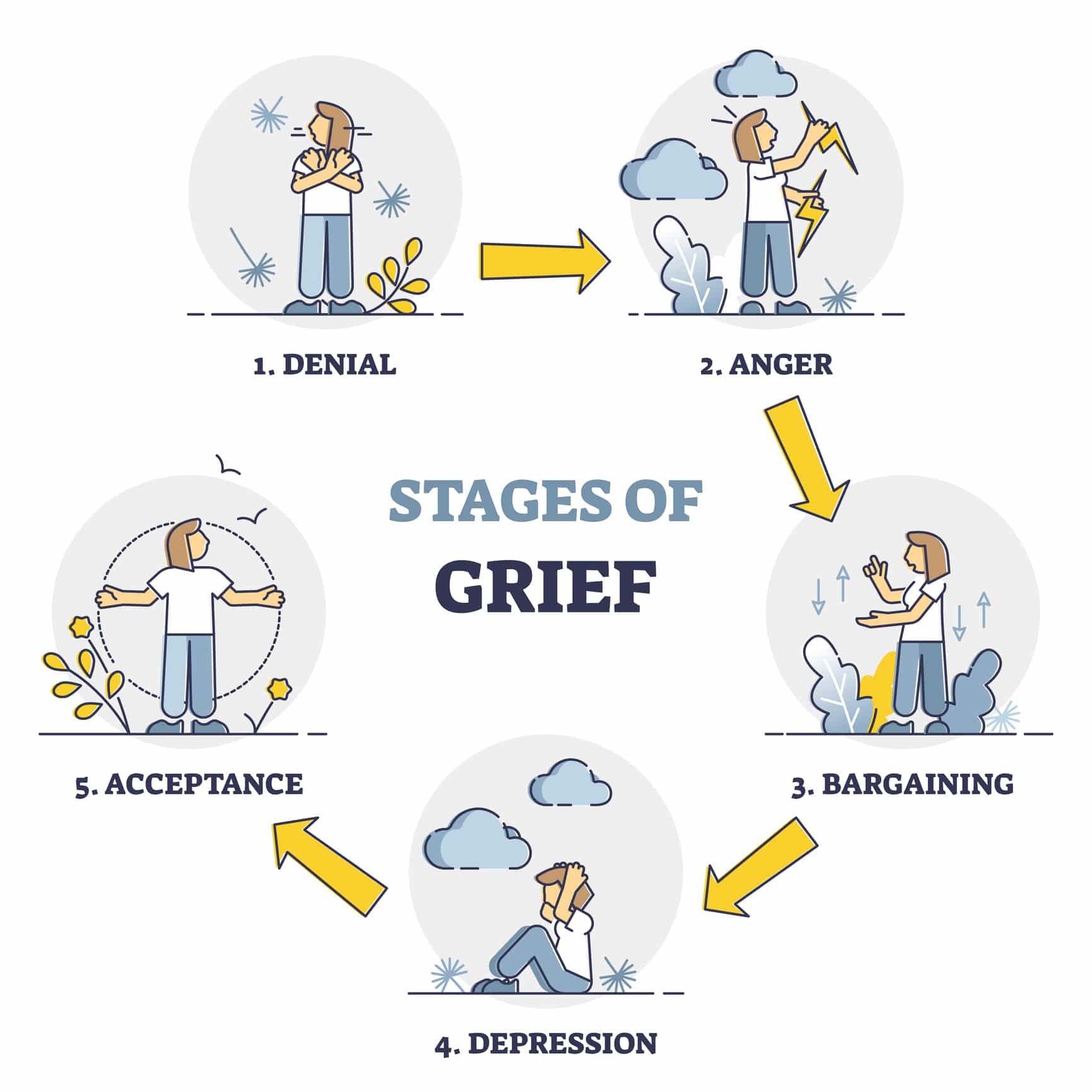

The Stages of Grief Aren’t What You Think

You’ve probably heard of the five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Here’s the thing—these stages aren’t a straight line. Kids don’t move neatly from one to the next and call it done. They might bounce between them, skip some, or experience several at once.

In foster care, we often mistake these normal grief reactions for bad behavior that needs to be corrected. But what if we looked at it differently?

Picture this: A teenager comes to your home and seems perfectly fine for a month. Then they start breaking curfew and arguing about everything. Instead of thinking “they’re being difficult,” try thinking “they’re starting to feel safe enough to show their pain.”

That “acting out” might actually be the anger stage of grief kicking in. Their emotional system is finally beginning to process a huge loss.

What Children in Care Are Really Grieving

Every child in foster care has experienced separation trauma—even when they were removed from unsafe situations. They’re not just missing their parents. They’re grieving:

- Their bedroom, their neighborhood, their school

- Friends they can’t see anymore

- Pets they had to leave behind

- Family traditions and inside jokes

- Their role in the family (maybe they took care of younger siblings)

- Their sense of identity and belonging

A 10-year-old who used to help her little brother get dressed every morning isn’t just missing her parents—she’s grieving the loss of being a big sister, a protector, someone important.

Why “Just Give Consequences” Doesn’t Work

When children act out because they’re grieving, traditional consequences often make things worse. Imagine if your best friend snapped at you right after losing a loved one. You wouldn’t ground them—you’d understand they’re hurting.

The same patience we show adults in grief is what children need. Their challenging behaviors are often their way of saying “I’m in pain” when they don’t have the words or emotional skills to express it directly.

Common Grief Triggers (And How to Help)

Grief hits when you least expect it. The child in your care might have a meltdown during:

- Moving day – Even moving to a “better” placement means losing the familiar

- Holidays – These highlight how different their family looks now

- School projects – “Bring a baby picture” can be devastating when all your photos are gone

- After visits with birth family – Coming “home” to your house can feel confusing and sad

- Random Tuesday afternoons – Sometimes grief just hits

What helps:

- Listen and reflect back what they’re feeling: “It sounds like you really miss your dad.”

- Help them name their emotions: “That sounds frustrating and sad.”

- Don’t try to fix it or talk them out of their feelings.

- Let them know that missing their birth family doesn’t hurt your feelings.

The Power of Staying Put

Here’s something crucial: Every time a child moves to a new placement, their grief process starts over. They have to adjust to new people, new rules, new everything—all while still processing their original loss.

Multiple moves don’t just disrupt healing; they create more trauma. Each move tells a child’s nervous system: “You’re not safe here either.”

Providing stability doesn’t mean never letting them be sad. It means creating a safe place where they can feel all their big emotions without fear of being sent away again.

What About Foster Parents’ Grief?

Let’s be honest—you’re grieving too. When a child reunifies with their birth family, you might feel overwhelming sadness, even when you know it’s the right outcome. You might feel guilty for being sad about what’s supposed to be good news.

This is called “disenfranchised grief”—grief that society doesn’t recognize or validate. Your feelings are real and normal, even if others don’t understand them.

The Goal Isn’t to Stop the Grief

We can’t eliminate grief from foster care—and we shouldn’t try. The goal is helping children process it in healthy ways.

Healthy grief happens when children:

- Feel permission to miss their birth family

- Have adults who don’t take their emotions personally

- Learn that big feelings are normal and temporary

- Feel safe expressing pain without being punished for it

Changing Your Perspective Changes Everything

Understanding grief doesn’t make foster parenting easier, but it makes the hard moments make sense. When you understand that a child’s “attitude” might actually be grief, you can respond with curiosity instead of frustration.

Instead of asking “How do I make them stop?” try asking “What are they trying to tell me?”

This shift creates the emotional safety children need to heal. And here’s the beautiful truth: When children grieve in foster care, it means they were loved. They formed attachments. They had relationships that mattered.

Honoring their grief honors their whole story—and helps them move toward healing.

This post was created using text, tips, and resources from the following tip sheets: